Empathy Means Not Saying “At Least”

“At least he had a good life.”

“At least you have your child.”

“At least you’re in good health.”

If any of these phrases sound familiar to you, then you’ve probably experienced profound grief or loss, or another strong, negative experience. In these difficult times, we want friends and family to surround us, sharing their comfort and supporting us in our stormy season of life.

Too often, however, our friends are at a loss for how to comfort us. They want to alleviate our pain. It distresses them to see us in such hurt. They don’t know the right words to say.

Our support network feels helpless at a time when it wants most to care for us.

How does this desire to help manifest in our time of need? With the phrase “at least.” Intended to comfort, our support network employs this phrase in an attempt to relieve our suffering. By pointing out something positive, the thinking goes, they can help us improve our mood and reduce our suffering.

It doesn’t work that way.

By pointing out this positive item, it feels to the sufferer as though we are negating the genuine pain they are experiencing. We minimize the experience the other person is going through. No matter how good our intentions are, we slight the one we care about, love, and want to help.

It’s unintentional and a reflex. I know that because I fall victim to at leasting people, too. I do it most often in my support groups when someone is going through a painful moment. “Well,” I might say, “I know it’s a difficult situation, but at least your husband is still talking to you.” No matter how much I am validating their experience in the first part of that statement, I’m still minimizing the severity of the situation.

Many times, we think we are expressing empathy. “I know this sucks, but…” But empathy is about more than saying “I know how you feel.” That’s sympathy. Empathy is about getting into the pain with the sufferer and allowing them to experience the feelings they have. It’s letting the storm rage through their bodies and minds and being willing simply to listen or hold them as they cry.

I saw this as a teen when my sister died unexpectedly. My parents were (and still are) fairly prominent in their faith community, so when they told my sister’s softball coach why they were pulling her from the game early, the word spread like wildfire. I mean, it was ridiculous. In the days before cell phones, our phone was ringing before they even returned home with my sister.

Empathy is about getting into the pain with the sufferer and allowing them to experience the feelings they have.

Two other couples formed a part of a triad with my parents. In a very short period of time, they were at our house with the parish priest, also a family friend. I saw them sitting in a circle on the deck, my father with his head in his hands, leaning onto his elbows.

It was silent. No one spoke. For a long time. They sat there with my parents, allowing them to process their emotions and grief. They were there to love and support, not direct or guide. They let their feelings flow through everyone in that circle.

There was no prayer for healing and mercy or to feel God’s grace in this painful moment, although all are devout Catholics. No one suggested that “at least” my parents had other children.

In fact, at one point, my father raised his head and said, “I have three children, now. I have to remember that. I have three children.” At this moment, the group spoke in chorus: “Oh no, Ronnie. You will always have four children. Always. Her death doesn’t take away from that.”

That’s empathy. None of them had lost a child. None of them could personally identify with the type of grief my parents experienced during that time on the deck. It didn’t matter. I once heard Brene Brown describe empathy as “getting in the hole with the other person and sharing their experience.” That’s what those friends did: they climbed down into the hole with my parents and shared as much of the experience as they could.

This is different from the sympathy our family received from others in the community. They would give us a hug, ask us how we were doing, and send a casserole. “At least you got the time you did with her,” I heard more than once. “She was a special person.”

At that moment, I didn’t care how much time I’d had with her. All I could see were the gaping, yawning years in front of me that I wouldn’t have with her. In the depths of my grief, that note of positivity was unhelpful and unwanted. And frankly, it pissed me off.

Their friends climbed down into the hole with my parents and shared as much of the experience as they could.

There is a time for at least and situations where it is helpful. As we work through the initial depths of our grief or loss, we are able to come up for air and start looking at the experience from a new angle. It may take a day or so to process the fact that we were fired from a job; after that, we can look at the situation and say, “Well, at least I have this certification,” or “at least I have some savings.” This shift in perspective is useful and helpful; we are looking at the facts of the story and painting a bigger picture than the one we first saw.

Our friends and family can draw our attention to those positive notes, further broadening our growing perspective.

My sister’s passing was awful. It impacted every part of my life. While I still miss and grieve her death, now I can say, “At least I know what others go through.” I can express a level of empathy that others can’t. She had a rough life, and while I don’t have a crystal ball, I doubt it would have gotten easier for her. At least she was spared that pain. At least she was released from the pain she was already in.

I can appreciate that now, with the distance of time and therapy.

And now I know what little help an at least is in those most challenging moments.

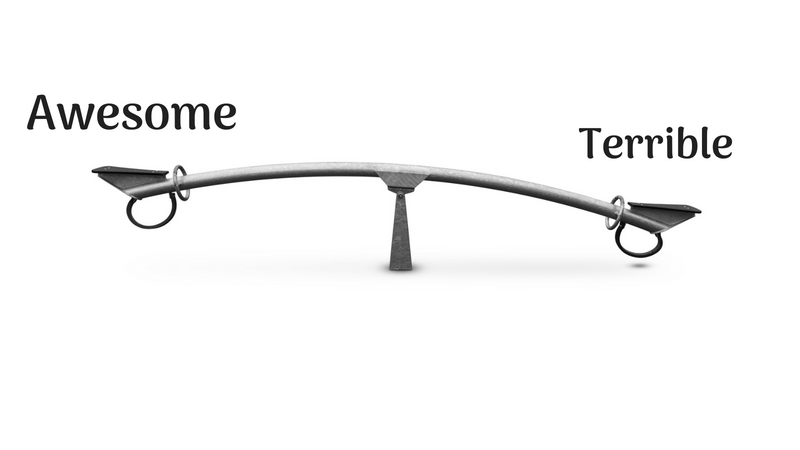

The difference between sympathy and empathy lies in at least.

What’s a time you’ve expressed empathy? How did you do it?

Looking for daily inspiration and community? Join our warm and supportive Facebook group!